A paper on ABO-incompatible transfusion and causes published in the British Journal of Haematology aimed to explore the causes and frequencies of ABO-incompatible red blood cell transfusions (ABO-it) in the United Kingdom (UK), France, and Germany. Specifically, the authors of the ABO-incompatible transfusion and causes study compared, “the effectiveness of existing safety measures in these jurisdictions considering possible improvements or modifications by learning from the practice of others, taking human factors into account [from 2013-2022.] An ABO-it with no measurable deleterious reaction in the recipient was classified as a serious adverse event (SAE). An ABO-it resulting in a reaction was classified as a serious adverse reaction (SAR) [ and graded on a four-point scale]: moderately severe (grade 1 SAR), severe and/or long-lasting (grade 2 SAR), life-threatening (grade 3 SAR) and death (grade 4 SAR).”

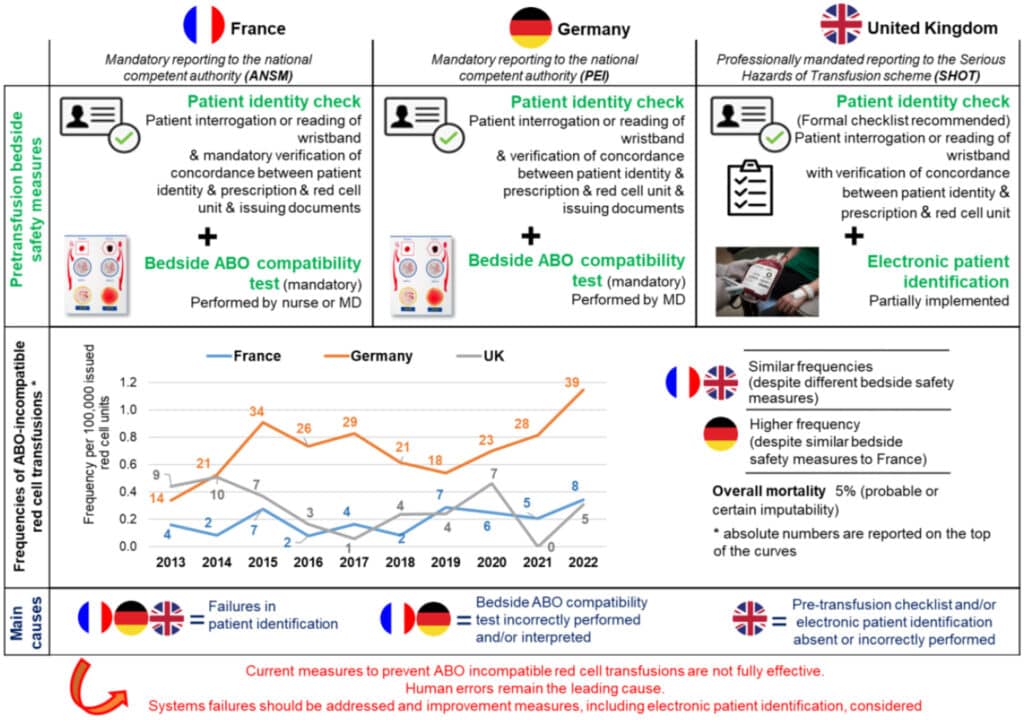

The authors of the ABO-incompatible transfusion and causes paper noted that French and German bedside preventative measures included, “positive patient identification check (as well as the verification of prescription, unit label, and issuing documents), all typically non-electronic to date, as well as an ABO compatibility test. These tasks are performed in France by a nurse (mostly) or a physician and in Germany by a physician or under his/her direct supervision and responsibility [while] in the UK, the pretransfusion check, performed at the bedside by registered healthcare professionals requires an exact match of the details on the patient identity wristband (positively confirmed by the patient if possible), the label attached to the unit and the transfusion prescription.”

The ABO-incompatible transfusion and causes study found that, “47 ABO-it were reported in France, 253 in Germany, and 50 in UK. The annual number of ABO-it varied from 2 to 8 in France, from 14 to 39 in Germany, and from 0 to 10 in the UK.” The researchers stated that, “[o]verall frequencies of ABO-it were 0.19 (SD: 0.09)/100,000 in France, 0.71 (SD: 0.23)/100,000 in Germany, and 0.28 (SD: 0.17)/100,000 in UK. The authors discovered that France and the UK exhibited similar frequencies of ABO-it despite different bedside safety measures, whereas Germany had a higher frequency [and the researchers noted that] Implementation of mandatory ABO-it reporting only one year before initiation of the study period probably resulted in early transient underreporting in Germany. [The] most frequently reported ABO incompatibility involved a group A red cell unit to a group O patient (France, 72 percent; Germany, 62 percent; [and the] UK 50 percent).”

Additionally, the ABO-incompatible transfusion and causes paper found that, “SAE was observed in 21 percent of ABO-it in France, 17 percent in Germany, and 40 percent in the UK. In France, grade 1 and grade 2 SAR were the most common each accounting for 26 percent of cases. In Germany, grade 2 SAR (46 percent) were the most common followed by grade 1 SAR (19 percent). Conversely, in the UK, SAR grade 1 were most common (30 percent) followed by grade 3 SAR (18 percent). No grade 4 ABO-it SAR was reported in France, while 19 grade 4 (9 percent) (with imputability considered as certain in 16, probable in two and possible in one) were reported in Germany and three grade 4 (10 percent) (with imputability considered as probable in one and possible in two) were reported in the UK.” The most common cause of ABO-incompatible transfusion in all three places was, “erroneous patient identification, that is, where the red cell unit was issued for another patient (n=152; 63 percent). Additional errors included wrong selection of the unit at the time of issuing (n=74; 31 percent), and incorrect recipient ABO grouping (n=14; 6 percent). Wrong donor ABO determination was very rare (0 to 1.5 percent) and wrong labe[l]ing of ABO group on the blood bag was not identified in this study.” The authors also explained that in France, “bedside ABO compatibility test was performed in 42 (89 percent) cases and incorrectly performed and/or interpreted in 41 of these. Among evaluable cases in Germany (n=53, 21 percent), the test was performed in 47 (89 percent) cases and incorrectly performed and/or interpreted in all these cases. [In the UK,] of the 50 ABO-it cases, only five (10 percent) stated they had a checklist in place for the administration of blood at the bedside, 14 (28 percent) did not have one and 31 (62 percent) did not answer the question. Twelve (24 percent) ABO-incompatible transfusion cases could not have been detected by beside safety checks as they were due to sampling or laboratory errors (four wrong blood in tube (WBIT), two testing errors and six component selection errors).”

The authors of the ABO-incompatible transfusion and causes study concluded that, “[o]ur results further corroborate previous findings that there is no single reliable, systemic safety measure that can prevent all ABO-it. All available measures depend upon staff performing them correctly. With these considerations in mind, one may conclude that the bedside ABO compatibility test, as currently performed in France and Germany, is time-consuming, complicated to execute and prone to error. Improvements should, therefore, be considered, such as the development and further implementation of electronic information systems (EIS) throughout the entire transfusion process, including electronic patient identification at the bedside with increased consideration of human factors. Further reducing the risk of ABO-it must remain a transfusion safety priority. Increased investment in EIS across the whole transfusion chain will contribute to a safer transfusion.”

Citation: Mirrione-Savin, A., Aghili Pour, H., Swarbrick, N., et al. “Frequencies and causes of ABO-incompatible red cell transfusions in France, Germany and the United Kingdom.” British Journal of Haematology. 2024